Three Ways to Control Depth of Field

Depth of field (DOF) refers to the amount of a scene in the “sharp” range. Shallow DOF is typically characterized by heavily blurred backgrounds that you might see in outdoor portraits. Deep focus (opposite of shallow DOF) is typically characterized by tack sharp landscapes with no visible blur.

The most widely accepted method for controlling DOF is aperture, or f-number. This is certainly a feasible and convenient way to control DOF, but there are other factors at play. Just like exposure is controlled by three factors (ISO, shutter speed, and aperture), DOF is controlled by three main factors. Let's take a look at these three factors and how you can use them to your advantage.

The examples shown below were taken on a 1.5x crop factor dSLR and the stated focal lengths are actual focal lengths of the lens rather than a full-frame equivalent.

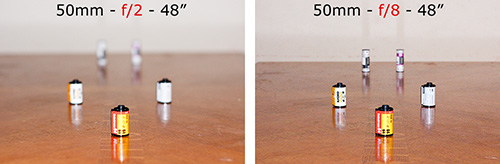

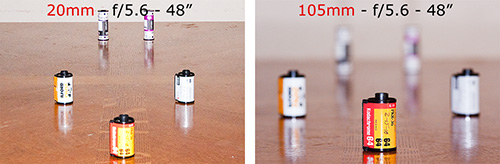

F-NUMBER

The f-number is probably the most widely known and used method of controlling DOF. Most intermediate/advanced cameras have “aperture priority” which allows you you set the f-number. If you've toyed with this mode on your camera, you probably found that lower numbers result in a narrow depth of field (blurry background), while higher numbers result in a wide depth of field (everything in focus).

F-NUMBER ⇓ == DOF ⇓

F-NUMBER ⇑ == DOF ⇑

TRY THIS: With a “normal lens” (40-80mm range), find a subject about 5-10 feet away from you and make sure there's some background object(s) in view behind it. Use your aperture priority and set the lowest f-number you can, and take a shot focused on the main subject. Now stay in the same spot and use the same focal length, but set the highest f-number you can (without bringing your shutter speed too low), and take another shot focused on the main subject. When you compare the two, the main subject should be in focus for both, but you'll see a difference in the background blur or the amount of focus on objects in the near distance.

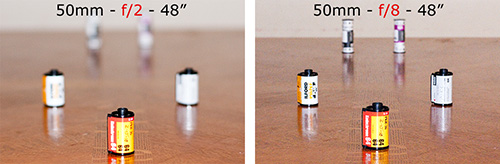

SUBJECT DISTANCE

Another way to control depth of field is to change your distance from the subject in focus. If you've ever shot macro, you know that the DOF is extremely narrow for 1:1 magnification. This is because you're so close the subject. On the other hand, if you've shot landscapes you'll know that it doesn't take much stopping down of the aperture to get everything in the distance nice and sharp. This is because you're so far from the subject.

DISTANCE ⇓ == DOF ⇓

DISTANCE ⇑ == DOF ⇑

TRY THIS: With a “normal lens” (40-80mm range), set your aperture to a value around f/4 or f/8. Again, find a subject that has some background element in view. Now get as close as your autofocus will allow you and take a shot. Keep the same focal length and the same f-number, but back up about 5-10 feet. Focus on the subject again and take a second shot. When you compare the two, you should see a difference in the depth of field by the amount of background blur.

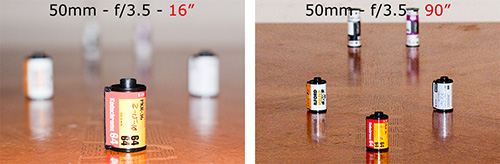

FOCAL LENGTH

The last factor in your control for DOF is the focal length of the lens you decide to use. Telephoto lenses have a shallow depth of field as compared to their wide angle counterparts. Anybody out there have a sub-20mm lens? It's pretty hard to get background blur, right? Any super-telephoto shooters out there? Just the opposite.

FOCAL LENGTH ⇓ == DOF ⇑

FOCAL LENGTH ⇑ == DOF ⇓

TRY THIS: Use a zoom lens that reaches from wide angle to telephoto (something like an 18-200, 28-135, etc.) or use two lenses (wide angle and telephoto). Again, find a subject that has some background element in view. Position yourself approximately 5-10 feet from the subject and set your aperture in the low-mid range (f/4-8, but make sure to find something that can be used for both lenses). Take the first shot with the wide angle lens or at the shorter focal length of the zoom lens. Now, hold your position and your f-number, and switch to the telephoto or use the longer focal length of the zoom lens and take the same shot with focus on the same subject. You should see a wider depth of field with the shorter focal length.

PUTTING IT INTO PERSPECTIVE

All this technical stuff is fine and dandy, but how does it translate to real world photography? The answer depends on what you're shooting with and what you're shooting at.

If you have a compact camera with no manual controls and you want a shallow DOF (say, for portraits)… zoom in all the way, get as close to your subject as possible (still preserving a decent composition), and take the shot. Also, less light will force the camera to use a smaller f-number and decrease the DOF. If you want a wide DOF (say, for landscapes)… zoom out all the way, get far away from your subject, and take the shot. Also, more light will force the camera to use a higher f-number and increase the DOF.

On the other hand, if you have a dSLR with manual controls and you want a shallow DOF… use aperture priority, set your f-number low (f/2.8-), get close to your subject, and/or use longer lenses. If you want a wide DOF… set your f-number high (f/16+), step back from your subject, and/or use wide lenses.

If you want to do some theoretical calculations on this topic, check out this handy Depth of Field Calculator. You just choose your camera, focal length, f-number, and subject distance. The calculator outputs your DOF, hyperfocal distance, and circle of confusion.

Links from around the web:

Back to Basics – Depth Of Field

Aperture: How It Affects Your Photography & Why You Should Care

Photography 101.5 – Aperture

HowTo: Use The Depth-Of-Field Preview On Your Camera

ANY OTHER TIPS?

How do you prefer to control your DOF? Any SLR shooters out there have a set of numbers that work well for narrow and wide DOF? How about some good examples of DOF in either extreme? We'd love to see 'em!

Also — any questions on this stuff? I might be jumping over a few concepts, so let me know if anything doesn't make sense.

Emil Sit

March 9, 2010With regards to point 2, take a look at this nice article from Luminous Landscape, Do Wide Angle Lenses Really Have Greater Depth of Field Than Telephotos?

Another really great article is Depth of Field and the Small-Sensor Digital Cameras by Bob Atkins on Photo.net. One thing this article points out (among the detailed math) is that you can use sensor size to control depth-of-field. Medium format will have less DoF than a P&S with a tiny sensor for the same field of view.

D. Travis North

March 9, 2010As always, Brian, great job simplifying a potentially demanding topic. Too many people focus on details that aren’t initially important. Many others don’t encapsulate the entire subject at hand – they might focus on the aperture as a means, for example, without discussing the other alternatives.

Sean Phillips

March 9, 2010Really well done on this one Brian. You’ve made it easy to see the differences and how to easily achieve the desired effect.

Brian Auer

March 9, 2010Thanks guys, I’m just hoping I didn’t forget some important piece of information or screw up some wording in there!

Sean Phillips

March 9, 2010Emil, I’ve read that article before and while it is technically correct, it is still flawed.

For those that haven’t read it, the author shows a series of images, made with different focal lengths, in which the size of the main subject in the image doesn’t change. It’s an interesting read, and any DOF calculator will show that his argument is correct.

However, that’s not how people shoot. Most people will be standing in one spot and will shoot an image using one lens or another (or one zoom lens at different focal lengths). They won’t, or can’t, try to keep the subject the same size. Brian’s example images above are much more representative of how people actually shoot. Clearly there is a difference in the DOF in the two images taken with different focal lengths from the same spot.

Brian Auer

March 9, 2010I was wondering when somebody would bring up the sensor size thing. It’s absolutely correct, but I left it out of this article for a reason: sensor size is not generally something you can swap out or modify without moving to an entirely different camera. The ones I did mention (f-number, distance, and focal length) are all things that can be modified “on the fly”.

Thanks for the link on point 2 also, it’s a good article. One thing to keep in mind when I say “change your focal length to change your DOF” — that works if you keep my other 2 points constant (distance and f-number). If we throw out distance and include framing (while still holding the f-number), then focal length loses its effect because the framing is a combination of focal length and distance.

Darken

March 9, 2010Nice article, Brian, as ever. Shift / tilt lenses, if you can afford them (!), are another fantastic way of limiting DoF, or increasing it in macro-photography. I’ve tried (with various success rates) using one to isolate features in landscape photography… A cheaper method is the lensbaby route, which I still love.

Brian R

March 9, 2010I’ve found that some (most? all?) compact cameras allow you to set a specific ISO. This gives you another potential control. High ISO => small aperture => greater DOF, and vice versa.

mustanir

March 15, 2010Points 2 and 3 are quite related, if you do the maths. Focal length and focus distance are factors which affect the real factor on which depth of field is based – magnification. Increasing your focal length increases your magnification, as does getting closer. Just a bit of technical clarification really, most of us don’t think of our lenses in those terms so looking at focal length and distance is much more intuitive.